“Brace Yourself: A Second Trump Presidency Could Transform America’s Courts Forever—Find Out How!”

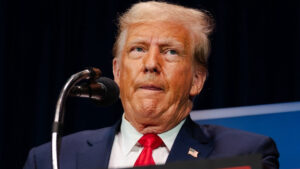

Photo: The Washington Post/Getty Images

The name “Donald Trump” is synonymous with a kind of goonish incompetence. This, after all, is the same man who once suggested that it may be possible to cure Covid-19 by injecting yourself with bleach.

During Trump’s presidency, however, at least one part of his White House bore little resemblance to the stumbling, bumbling operation that might praise neo-Nazis as “very fine people” one day then tweet out a threat to start a nuclear war the next. Trump’s judicial selection process was efficient, professional, and stunningly effective in placing many of the nation’s most intellectually gifted right-wing ideologues on the federal bench.

As a result, the GOP now has a judicial machine geared toward replacing longstanding legal principles with Republican policy goals.

Since Trump’s three appointees gave Republicans a supermajority on the Supreme Court, the Republican justices have behaved as though they are all going down a GOP wishlist, abolishing the right to an abortion, implementing Republican priorities like a ban on affirmative action, and even holding that Trump has broad immunity from prosecution for crimes he committed using his official powers while in office. To be clear, right-wing litigants are not winning every case they bring before the justices, but on issues where the various factions within the Republican Party have reached a consensus, the Republican justices reliably align with that consensus.

The lower courts, meanwhile, have become incubators for far-right policy ideas that often go too far even for a majority of the members of the current Supreme Court. Think, for example, of Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk’s failed attempt to ban the abortion drug mifepristone. Or an astonishing decision by three Trump judges that declared the entire Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) unconstitutional. Both of these lower court decisions were rejected by the Supreme Court.

That there are some positions too far right even for many Republican members of the Supreme Court is a reminder of the diversity that exists among Trump’s judges. Some, like Justices Brett Kavanaugh or Amy Coney Barrett, are fully committed to using the courts to implement a long list of Republican ideas. But this cohort of judges also rejects at least some right-wing legal theories that would have catastrophic consequences for the country.

Both Kavanaugh and Barrett, for example, rejected the legal attack on the CFPB. They joined an opinion explaining that the plaintiffs’ legal theory had no basis in constitutional text or history, but they may also have been motivated by the fact that this theory could have triggered an economic depression if it had prevailed. Kavanaugh and Barrett also backed Trump’s claim that he has broad immunity from criminal prosecution for crimes committed in office, but on the same day they rejected a Texas law that would have given that state’s Republican legislature extraordinary authority to dictate what the media must print.

The other faction of Trump’s judges is more nihilistic. They include Kacsmaryk, who has turned his Amarillo, Texas, courtroom into a printing press for court orders advancing far-right causes. The nihilistic faction also includes judges like Aileen Cannon, the Trump judge who has presided over one of Trump’s criminal trials (and behaved like one of his defense attorneys), much of the far-right United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, and Trump Supreme Court appointment Justice Neil Gorsuch.

Gorsuch, for example, saw nothing wrong with the case against the CFPB. In a case involving hundreds of billions of dollars worth of transactions the federal government used to stabilize the US housing market after the 2008 recession, Gorsuch also voted for an outcome that risked triggering an economic depression.

Gorsuch is one of two justices who wanted to overrule New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), a seminal First Amendment decision that is the backbone of press freedom in the United States. And, even on a Court that is often hostile to voting rights, Gorsuch stands out: In a 2021 opinion, he would have neutralized the federal Voting Rights Act almost in its entirety.

Trump has given some oblique signals that he’s soured on the more pragmatic wing of judges. Among other things, the former president reportedly harbors particular resentment toward Kavanaugh, after Kavanaugh refused to back Trump’s effort to overthrow the 2020 election. Trump reportedly thinks Kavanaugh owes him after Trump continued to back Kavanaugh’s nomination even after the future justice was accused of sexually assaulting a woman while in high school.

Still, Trump has yet to signal definitively whether his judicial nominees would reflect the full diversity of Republican lawyers if he were returned to office, or whether he would instead draw more heavily from the more nihilistic cohort in a second term.

There’s nothing usual about Trump’s first-term judges — they’re just Republicans

Trump’s first term in office was a power-sharing arrangement between two overlapping anti-democratic movements, the MAGA cult of personality centered on Trump and a more overtly refined, legalistic movement centered in groups like the Federalist Society, an organization for conservative lawyers.

In this arrangement, Trump got the title of “president” and the trappings of office, but he largely delegated the power to select judges to longtime operatives within the conservative legal movement.

As a result, Trump’s judges looked more or less the same as the sort of judges who may have been appointed if former Gov. Jeb Bush or Sen. Marco Rubio had become president in 2017.

Trump promised this would be the case while campaigning for president in 2016, saying, “We’re going to have great judges, conservative, all picked by the Federalist Society.”

At the time, many Republicans, who had long dreamed of ruling the nation from the bench in much the same way the Supreme Court does now, feared that Trump’s judges, like Trump himself, would be erratic and unreliable — or even worse, liberal. Trump allayed these fears in 2016, however, by releasing a list of 11 sitting judges and pledging to choose Supreme Court nominees from this list. All 11 names on the original list were reliably conservative judges in good standing with the Federalist Society.

Trump supplemented this list many times; none of his appointees to the Supreme Court — Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, or Barrett — were among the original 11. But the specific names mattered less than the message sent by the list. As the National Review said in an editorial last March, “Because Trump had never served in government and had little record of engagement with political ideas or activism, [the list] helped fill in the blanks for voters.”

After entering the White House, Trump took other steps to integrate the Federalist Society into his judicial selection process. Most notably, he chose Don McGahn, a longtime society member, as his White House Counsel — a role that gave McGahn considerable control over Trump’s judicial nominees. In 2017, responding to allegations that Trump outsourced his judicial nomination process to the Federalist Society, McGahn quipped that his own presence within the White House meant that “frankly, it seems like it’s been in-sourced.”

Guided by McGahn, the Trump White House picked judges heavy on the sort of credentials that legal employers often use to identify very promising young legal talent, including a degree from a highly ranked law school and whether the candidates had a prestigious judicial clerkship, a kind of one-year apprenticeship to a sitting judge. The biggest clerkship prize, at least for a young lawyer without any previous experience, is a clerkship for a federal appellate judge. About 80 percent of Trump’s appeals court nominees had such a clerkship on their resume.

Federal appellate clerks, meanwhile, compete for an even bigger prize: a clerkship with a Supreme Court justice. About 40 percent of Trump’s appellate nominees clerked for a justice.

By contrast, according to a recent paper by legal scholars Stephen Choi and Mitu Gulati, roughly 10 percent of President Joe Biden’s appellate judges clerked for justice, and about half of Biden’s appellate judges, themselves clerked for a federal appellate judge.

Meanwhile, in large part, because Senate Republicans blocked nearly all of Obama’s appellate nominees during his final two years in office, Trump came into the White House with an unusually large number of vacancies to fill, and he took advantage of this fact. As Choi and Gulati write, “In a single term, Trump appointed 54 judges at the appeals court level. Obama, in two terms, had one more, 55.”

So Trump had an unusually large impact on the federal courts, especially for a one-term president. He largely delegated the task of choosing judges to sophisticated right-wing operatives with a clear vision of what they wanted out of the judiciary, and those operatives successfully installed many judges with the sort of resumes legal employers drool over.

In short, Trump successfully filled the judiciary with reliable, high-achieving, Republican judges.

There are real differences between the GOP’s pragmatic and nihilistic factions, but they agree on a wide range of issues

Lawyers are trained, in the words of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct, to show “zeal in advocacy upon the client’s behalf.” A lawyer’s job is to advance the interests of that client, not to push for rules that are sensible or even morally defensible. If a lawyer is hired to defend a company that just poisoned thousands of innocent people, the lawyer’s job is, if possible, to get that company off scot-free.

So, by appointing lawyers of great skill to the federal bench, Trump did not select judges who were necessarily inclined to read the law in reasonable, or even plausible, ways. On the contrary, he picked individuals whose core skill was often persuading judges to read the law in unnatural ways in order to benefit the lawyer’s client.

Since joining the bench, many of Trump’s judges and especially his justices have behaved as zealous advocates for the Republican Party and its causes. In some cases, such as the Court’s “major questions doctrine” decisions — a series of cases in which the justices gave themselves the power to veto actions by agencies within the executive branch — or its Trump immunity decision, Trump’s justices embraced arguments that cannot be defended under any plausible theory of law.

In others, including the Court’s big abortion and affirmative action cases, Trump’s justices appear to be systematically identifying issues that have long divided the two parties and converting past Democratic victories into Republican wins.

Yet, while Trump’s judges are often reliable advocates for the GOP and its positions, they also reveal real disagreements within the Republican Party. And Trump often drew his first-term judges from both sides of this internal divide.

Traditionally, for example, the Republican Party has taken an expansive view of the First Amendment. In the early 2010s, the Supreme Court handed down a pair of cases protecting truly revolting speech, one of which involved a notorious church that protested a fallen marine’s funeral with anti-gay slurs and signs declaring “Thank God for Dead Soldiers.” Both cases were decided 8-1, with only Justice Samuel Alito taking a narrow view of free speech.

After Trump, however, Republicans splintered on whether they still support traditional free speech principles. After Texas and Florida GOP legislatures passed laws seizing control of content moderation at major social media outlets, the six Republican justices split right down the middle. Three of them (including Trump Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett) took the traditional view that the government may not tell media outlets what they must print. Three others, including Trump Justice Gorsuch, tried to rescue these unconstitutional laws.

There are other issues that divide Republican judges. In Republican National Committee v. Mi Familia Vota (2024) — a case, blocked by lower courts, involving an Arizona law that imposed various new restrictions on voters — Trump’s three justices split three ways. Barrett voted with the three Democrats to leave Arizona’s preexisting election rules intact. Kavanaugh voted (along with most of the Court) to make it marginally more difficult to register to vote in Arizona. Gorsuch, the furthest right of the three, voted to strip thousands of already-registered voters in Arizona of their ability to vote for president.

In any event, the fact that Republican judges and justices sometimes disagree with one another, especially in cases where the right-leaning litigant makes a particularly outlandish claim, shouldn’t surprise anyone. Republicans in all three branches of government frequently disagree on important questions of federal policy.

The divide between more pragmatic Republican judges like Kavanaugh, who tend to shy away from legal arguments that could cause turmoil or mass unrest, and more nihilistic Republican judges like Gorsuch, who embrace the potential for chaos, closely resembles the divide between relatively pragmatic figures like Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and more reckless lawmakers like the House Freedom Caucus. Just as McConnell often breaks with his party’s right-most flank on issues like the war in Ukraine, many of Trump’s judges reject the most aggressive legal arguments presented by the most far-right litigants.

But that doesn’t mean either faction is disloyal to its political party. Both factions reliably seek to advance Republican interests and causes, but one faction sometimes favors tactics the other believes to be counterproductive.

Trump is giving some signals that he will prefer the nihilistic faction if he gets a second term

Despite the political success of his 2016 list of potential Supreme Court nominees, Trump has yet to put out a similar list for the 2024 election. He has given few direct signals about which sort of Republicans he’d appoint if he achieves a second term.

That said, a few statements by the former president suggest that he prefers judges from the more nihilistic faction and may even view Gorsuch as too soft.

In a May interview with radio host Dan Bongino, for example, Trump praised Justices Clarence Thomas and Alito, for many years the Court’s most unapologetic right-wing Republicans, while offering a much more tepid view of his own justices. Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, Trump said, have “got to be stronger, they’ve got to be tough.” Meanwhile, Trump labeled Alito ‘very tough, very good,” and Thomas “great.”

Similarly, in journalist Michael Wolff’s 2021 book Landslide: The Final Days of the Trump Presidency, Trump said he was “very disappointed in Kavanaugh” and claimed that his appointee “hasn’t had the courage you need to be a great justice.”

Again, these aren’t the clearest possible signs that Trump will choose judges from the most extreme faction of the GOP if he becomes president again, but they certainly suggest he favors those judges, and may try to elevate others like them if given the chance.

If you want to know what a world with a nihilistic Republican majority on the Supreme Court would look like, examine the Fifth Circuit, a federal appeals court controlled by that faction that hears cases arising from Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The results aren’t pretty.

It was the Fifth Circuit’s decision striking down the CFPB that risked triggering a second Great Depression because that decision could have prevented banks from issuing new mortgages. The Fifth Circuit largely backed Kacsmaryk’s attempt to ban the abortion drug mifepristone. It effectively eliminated the right to engage in mass protest. It once held that a prisoner could be kept in a cell with such a thick layer of dried human feces on the ground that it made a crunching sound as the prisoner, stripped naked, walked across the floor.

And this is just a small sampling of the kind of far-right legal reasoning that routinely escapes this benighted court.

If elected president this November, Trump is almost certain to fill the bench with judges who are eager to implement Republican policies. The question is what type of Republicans he will favor: relatively pragmatic judges like Kavanaugh, or the chaos agents who dominate the Fifth Circuit?